Diamonds have been

used for various purposes throughout history. The first mention of diamonds in

ancient texts was in a Sanskrit manuscript written between 320 and 296 by a minister in northern India. While diamonds have been used for millennia, the history of studying their brilliance is shorter.

Around the 13th

century in Europe, diamonds became associated with monarchies and

aristocracies, set against pearls and gold as accent pieces. As centuries passed, diamonds became more prominent features in jewelry for the wealthy, which

was greatly due to the understanding of diamond faceting. When diamond faceting

was developed, the jewelers of the time found that the brilliance and fire of

the diamonds were greatly enhanced, making them more attractive to wear than

ever before. In the 17th century, the diamond became the small staple gemstone

in high-class jewelry. By the 18th century, they had also become the

most sought-after large gemstones. This increase in interest would have happened to a different degree if the brilliance of diamonds had not been studied.

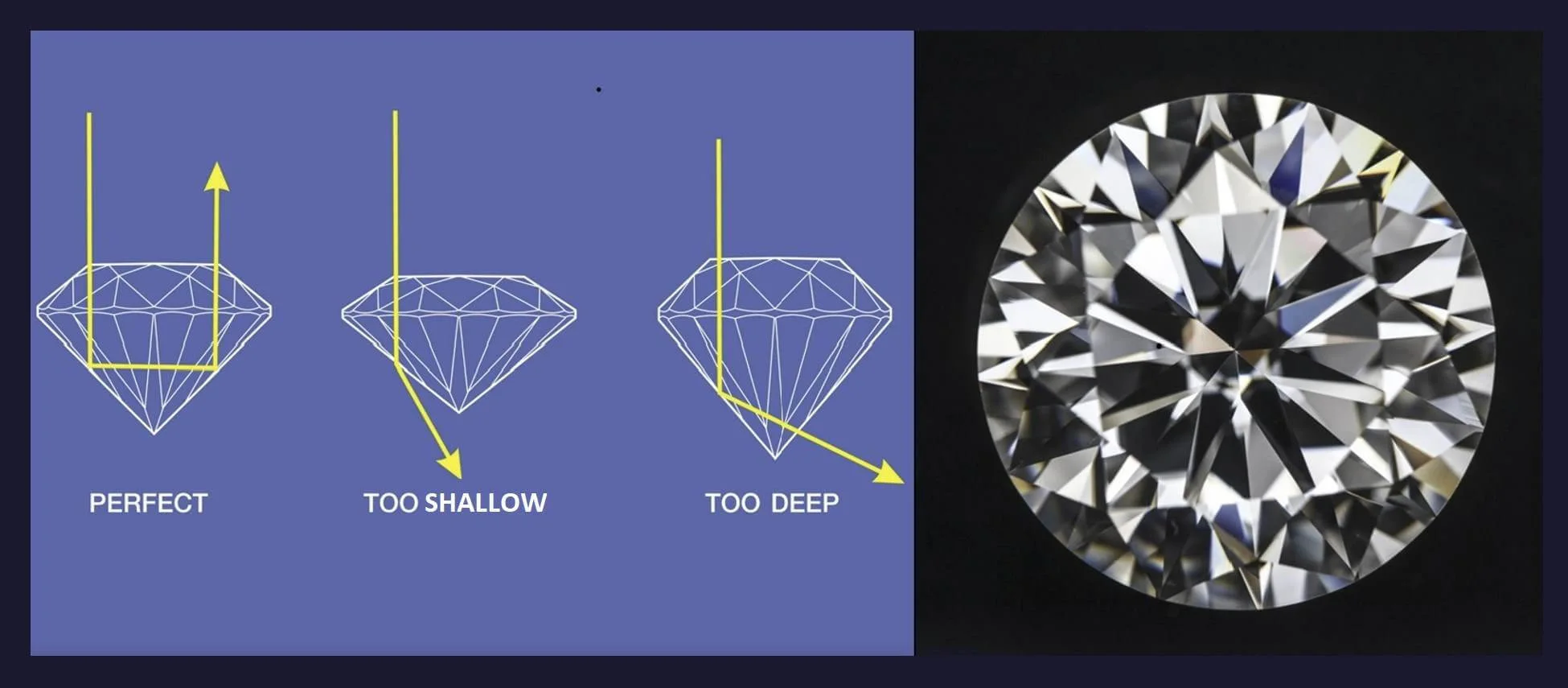

Since the more brilliance a diamond has, the more it reflects light, royals

wearing diamond pieces would sparkle, making them seem even more impressive

than they would have been otherwise.

While the world's

royalty tried to obtain diamonds throughout the centuries, it was only at the

end of the 19th century that the role of diamonds faced a change. The first

event that affected them was the discovery of immense diamond deposits in South

Africa in the 1870s. This meant that diamonds could be procured much more

efficiently than ever before, and you did not need to be royal to have one. The

other big event was that, following the fall of Napoleon III of France, the

French crown jewels were sold to Tiffany & Co. of New York and taken to the

United States. Under the electric and gas lighting that had been steadily

increasing around New York at the time, the brilliance of the diamonds was able

to show off to a level that had never been seen before.

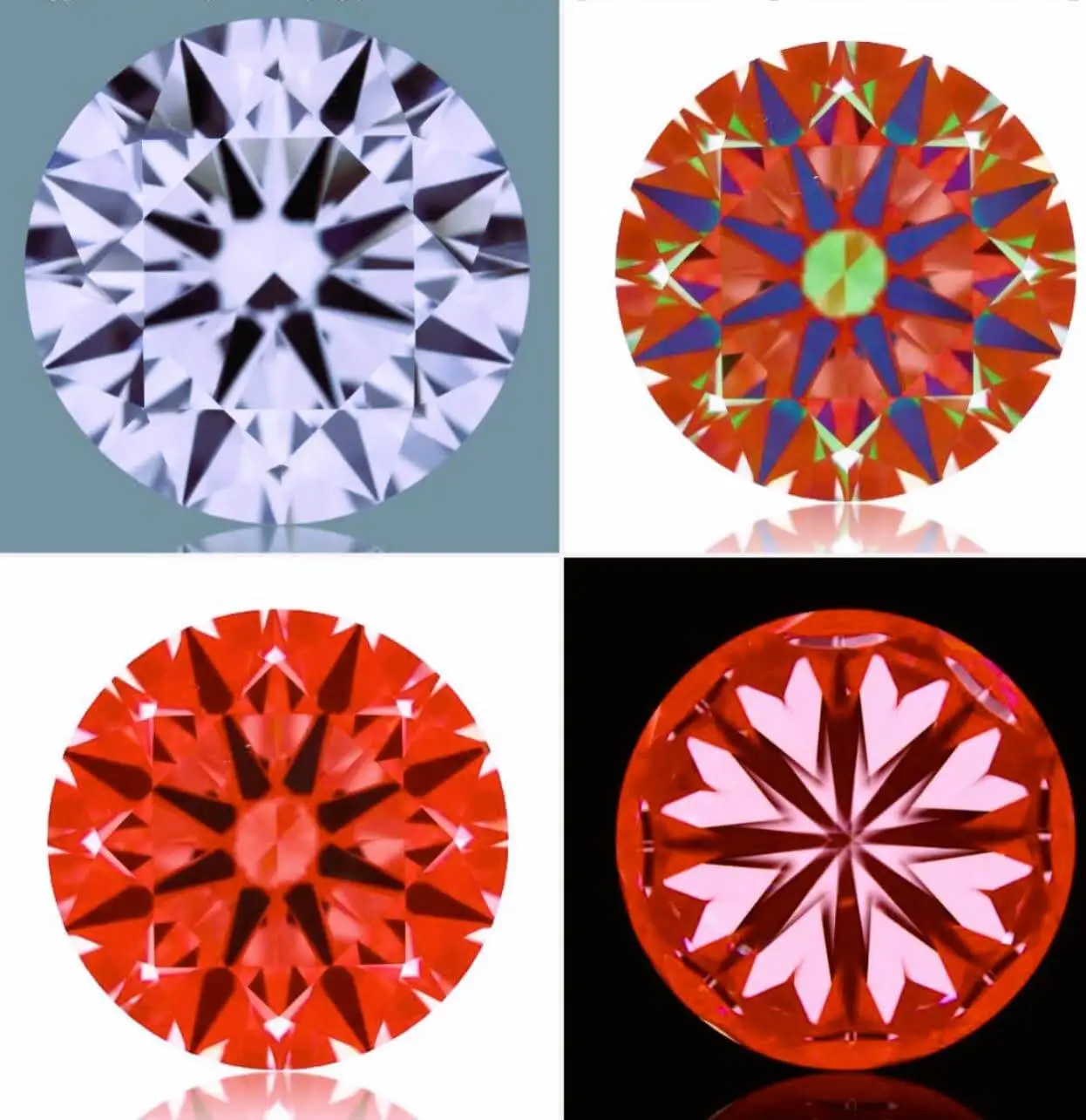

As a result of Tiffany & Co.'s discovery and presentation of the crown jewels, jewelers learned

the importance of displaying diamonds with the ideal illumination to make the

stones' brilliance stand out. Since where the light comes from will affect

the look of a diamond's brilliance, fire, and sparkle, most jewelers display

diamonds in bright spotlights. If the jeweler wants to present the diamond's

brilliance to the highest degree, they may use fluorescent illumination.

However, doing so may come at the cost of dulling the fire and sparkle of the

diamond.